Evangelicalism is Good for America

On a recent visit to the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, it struck me that it would be impossible for any branch of American Christianity to reproduce such a thing today. American Christianity—the soul of our nation—is fractured and insecure about its place in public life.

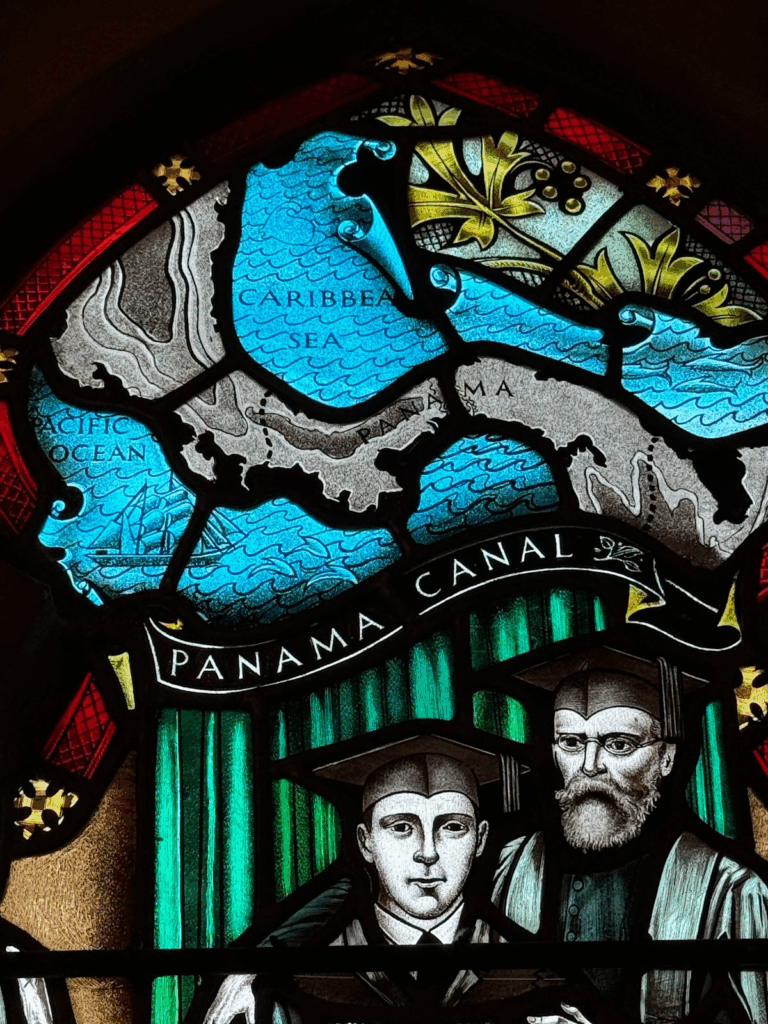

Founded by Southern Episcopalians in 1857, Sewanee sits on a bucolic 13,000-acre campus in the Southern Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee. Its campus architecture offers a rare, elevated celebration of rural Tennessee terroir. Local sandstone and limestone adorn its Southern Gothic buildings. History pours out of every little plaque and stained-glass window (of which there are thousands), commemorating a rich legacy ranging from Teddy Roosevelt’s campus visit and the Panama Canal to the scores of service academy graduates who fought in America’s wars. Here, pomp and circumstance come naturally; the chancellor of the College—who is also charged with being mayor of the town of Sewanee—dons a red velvet robe for high occasions.

Holding a commanding position at the edge of the Cumberland Plateau about ninety minutes southeast of Nashville, the campus—which the College calls “the Domain” in all official literature—takes in the town of Sewanee and the surrounding forests. On the western edge of the Domain, a massive cross watches over a dramatic point overlooking Winchester and the Elk River in the Southern Highland Rim of Tennessee.

Sewanee is, admittedly, a special place. But you can visit an Ivy League school, our National Cathedral, or the first hospitals and libraries in most major American cities and encounter a similar story. Everywhere, you will see signs of a once-vital faith that built with civilizational ambition—a practice that seamlessly blended piety and political leadership, high culture and localism, tradition and innovation.

Most Americans today have never experienced places built by elites who loved this country enough to bind themselves to it across generations. They believed they were stewards of something permanent: a Christian civilization in America that required institutions, beauty, memory, and continuity.

Readers of American Reformer are familiar with the story of America’s mainline Protestant denominations. Once the backbone of American public life, they hollowed themselves out over the twentieth century. In their desire to remain culturally respectable, they traded theological confidence for moral fashion. Doctrine softened into sentiment; authority dissolved into process; inheritance gave way to accommodation. The institutions survived, but their animating spirit did not. Cathedrals became museums, seminaries became activist training grounds, and universities retained their endowments while abandoning their souls.

Mainline Protestantism did not fail because it tried to shape civilization. It failed because it lost confidence in the Christian truths that made such shaping possible in the first place. Having surrendered its conviction in transcendent sources of authority, it could no longer justify its own authority—either to believers or to the broader culture.

American Evangelicalism, for all its spiritual vitality and its ample resources, has failed to replicate what the mainlines once achieved. On the whole, Evangelicals tend to build megachurches, not cathedrals; conferences, not elite colleges; platforms, not domains.

There are many explanations offered for this state of affairs. Some point to evangelical theology, where an emphasis on personal conversion deemphasizes institution building. Others cite class, noting that evangelicalism has historically been a middle-class movement rather than an elite-forming one. Still others blame broader cultural forces—expressive individualism, consumerism, and short-termism—that shape all American institutions, religious or otherwise.

Each of these explanations captures something true, but none fully accounts for the deeper failure. Evangelical Christianity has become uncertain—often self-consciously so—about whether its moral vision is good for the nation as a whole. In retreating from claims about the public good of Christian norms, evangelicals have also retreated from the responsibility to build institutions that embody them.

Civilizational Protestantism rested on a confidence that Christian faith was no mere private consolation or a sectarian preference, but a moral inheritance capable of ordering the common life. Its builders believed that Christianity could produce better leaders, more humane institutions, and a more just society. This confidence did not require perfection or coercion. It required the conviction that Christianity, rightly lived, was a blessing to the nation—and therefore something that ought to be publicly expressed, publicly defended, and publicly institutionalized.

By contrast, much of contemporary evangelicalism oscillates between withdrawal and reaction. It resists public responsibility out of fear of overreach, then lashes out when its influence wanes. What it lacks is not passion or conviction in the abstract, but confidence in the legitimacy of its own civilizational project. Without that confidence, institution-building appears either unnecessary or presumptuous.

This is why the question of renewal cannot be answered merely by appeals to faithfulness or growth. It must answer a more basic question: Do we believe evangelical Christianity is good for America? Not just true in the abstract, but formative of citizens, elevating of culture, and worthy of public trust.

So if one were asked what national renewal should actually look like—what a confident, public-minded American Christianity might produce—one could give worse answers than this: a Christianity once again capable of building institutions like the University of the South. Not as relics of a lost establishment, but as expressions of a faith that understands itself as a public good.

Recovering civilizational Protestantism ultimately means recovering the courage to act as though Christianity belongs not only in hearts and homes, but in shared civic life.

The question is not whether evangelicals have the resources to do this. It is whether they are prepared to believe, once again, that they should.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published at American Reformer.

Share This Story